What Is A Processed Food And Why They're Everywhere

What Is A Processed Food

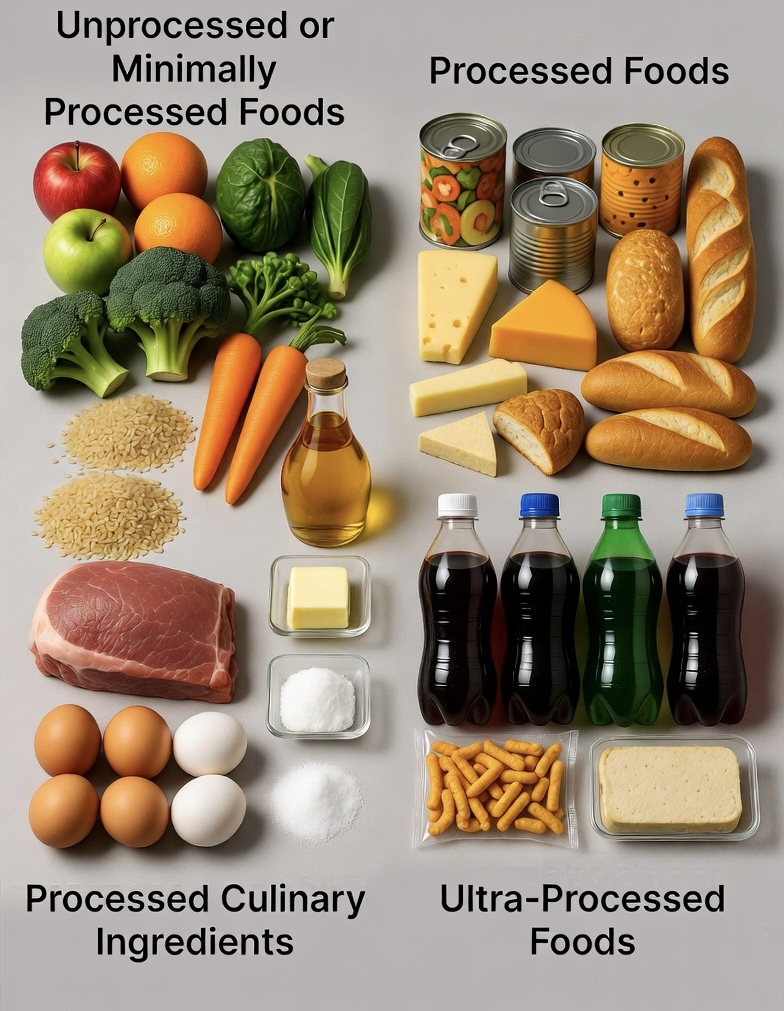

The answer to "What is a processed food" encompasses a wide range of products that undergo varying degrees of alteration from their natural state. The NOVA food classification system, developed by researchers at the University of São Paulo and widely referenced in global nutrition studies, groups foods into four categories based on the extent and purpose of processing. This system focuses on how foods are transformed after separation from nature—through physical, biological, or chemical methods—before consumption or use in meal preparation.

• Group 1: Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Foods

These are edible parts of plants or animals obtained directly from nature, with little to no alteration beyond basic preparation for safe consumption or storage. Processes may include cleaning, removing inedible parts, fractioning, grinding, drying, chilling, freezing, pasteurization, vacuum packaging, or non-alcoholic fermentation—but no additions like oils, fats, sugar, or salt.

You May be asking yourself, what is a processed food when the food is whole ? Here are a few examples of minimally processed foods.

Examples: Fresh fruits and vegetables (apples, carrots, potatoes), whole grains (brown rice, oats, corn kernels), fresh or frozen meat, poultry, fish, eggs, milk, nuts and seeds (unsalted/unsweetened), dried fruits or herbs without additives, fresh mushrooms, legumes (lentils, chickpeas), and plain water, tea, or coffee. These foods remain close to their original form and are typically used as the foundation for home-cooked meals.

• Group 2: Processed Culinary Ingredients

These are substances derived from Group 1 foods or nature through pressing, refining, grinding, milling, or similar methods. Their purpose is to serve as ingredients in home or restaurant cooking to prepare, season, or enhance dishes. They are rarely eaten alone.

What is a processed food when it comes to regularly used ingredients?

Examples: Oils (olive, sunflower, soybean), butter, lard, sugar (white, brown, molasses), honey, salt (refined or sea), starches (from corn or other plants), and syrups (maple). Combinations like salted butter fall here too. These support traditional meal preparation.

• Group 3: Processed Foods

These result from combining Group 1 foods with Group 2 ingredients, primarily to preserve them, enhance flavor, or increase durability. They usually involve 2–3 added ingredients and remain recognizable as modified versions of natural foods. Processes include canning, bottling, smoking, salting, curing, or fermentation.

Examples: Canned vegetables or beans in brine, cheeses, freshly baked bread, canned fish in oil or water, fruits in light syrup, salted or dried nuts, fermented items like beer or wine (non-ultra versions), and cured meats. These are often consumed as part of meals or simple snacks.

• Group 4: Ultra-Processed Foods

These are industrial formulations made mostly or entirely from substances extracted from foods, combined with many added ingredients (often 5+), including those not typically used in home kitchens like flavor enhancers, colors, emulsifiers, hydrogenated fats, modified starches, or artificial sweeteners. They are designed for ready-to-consume convenience, long shelf life, and high palatability through extensive processing.

Examples: Sodas and sweetened beverages, packaged snacks (chips, crackers), frozen pizzas and ready meals, sugary cereals, mass-produced breads/cakes/pastries, instant soups/noodles, pre-packaged lunch kits, hot dogs/burgers in fast-food form, ice cream, confectionery, and many flavored yogurts or drinks. These dominate modern convenience aisles.

Ultra-processed foods (Group 4) have become the most prominent category in contemporary food systems due to industrial-scale manufacturing.

Why Are Processed Foods Everywhere?

Several interconnected factors explain this dominance in the modern food supply:

• Economic and Production Advantages — Ultra-processed foods are produced at massive scale using low-cost ingredients (often derived from subsidized crops like corn, soy, and sugar), automated factories, and efficient supply chains. This keeps manufacturing costs low while enabling high-volume output with extended shelf lives through preservatives and packaging. In contrast, fresh whole foods require more frequent sourcing, shorter supply chains, and higher handling costs.

• Convenience and Shelf Stability — These products are ready-to-eat or heat, require minimal preparation, and resist spoilage for months or years. This appeals to busy lifestyles, urbanization trends, and environments with limited cooking facilities or time.

• Marketing and Retail Placement — Transnational food companies heavily promote these items through advertising, branding, and strategic shelf positioning in supermarkets, convenience stores, schools, and fast-food outlets. They often occupy prime real estate, making them more visible and accessible than fresh options.

• Supply Chain and Market Dynamics — Ultra-processed foods dominate grocery aisles (estimates suggest 58–75% of packaged staples in U.S. stores), food aid programs, and low-access areas like food deserts or swamps. Fresh whole foods can be harder to stock consistently due to perishability, transportation logistics, and lower profit margins for retailers/manufacturers.

• Global and Local Trends — As populations urbanize and incomes shift, demand for quick, affordable options rises. Industrial food systems prioritize profitable, scalable products, displacing traditional whole-food sourcing in many communities.

This widespread presence means ultra-processed foods often crowd out minimally processed or whole options, limiting everyday access and affordability for millions.

Our mission addresses this imbalance by delivering directly to families and communities facing these barriers.

Donate today to help expand access to real, minimally processed choices.